Rural Boulder, Utah, is a tiny town in the desert with only about 200 people. But every summer, something mystical happens there: a group of monks descends on the town for a week of Buddhism-focused activities. The monks hail from the Drepung Loseling Monastery, which was established in Tibet in 1416 and now has a monastery in India. They spend the week at the Boulder Mountain Lodge, co-hosted by Hell’s Backbone Grill next door, as part of a program called Mystical Arts of Tibet. Visitors to the lodge and grill at that time eat traditional Tibetan food, attend teachings and special blessings, and watch the creation—and destruction—of a sand mandala.—Jennifer Billock

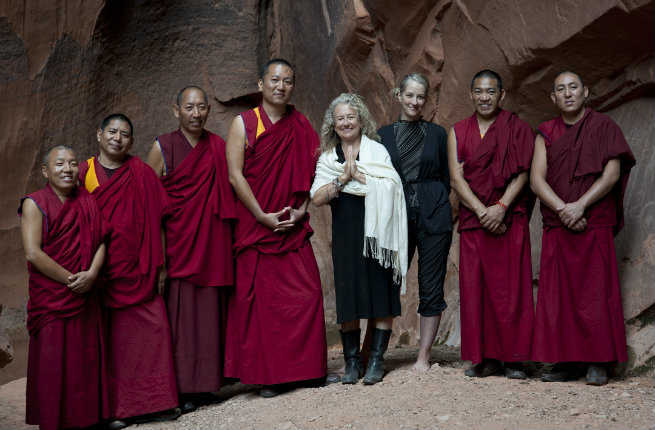

The monks of Drepung Loseling Monastery

Thanks to the Mystical Arts of Tibet program, some of the Drepung monks take an annual 10-month tour around the world—a trip that takes them to the small town of Boulder in Utah. The purpose of the visit is threefold: to use sacred art to contribute to world peace and healing, to bring awareness to the endangered Tibetan civilization, and to support India’s Tibetan refugee community. Different monks are selected every year for the tour.

Hell’s Backbone Grill embraces Buddhism

Hell’s Backbone Grill in Boulder co-hosts the monks while they’re in town. The grill is an organic farm-to-table restaurant focusing on regional cuisine. Co-owners Blake Spalding (wearing the white scarf) and Jen Castle (to Blake’s right) are Buddhists and run the restaurant accordingly—focusing on sustainability, social responsibility, community responsibility, and environmental ethics. What they don’t grow and source from their own farm comes from local heirloom orchards and nearby ranchers.

Preparing for a performance

The monks prepare for a musical performance with traditional instruments. This monk is using a gyaling trumpet, a type of flute made from hardwood. The holes are similar to a typical flute, with one in the back and seven in front. Performances put on the by the monks pay homage to the traditional celebrations of spiritual festivals at Tibetan monasteries, when everyone gathers in the courtyard for several days of music and dance.

The monks take the stage

Another traditional instrument used in the monks’ performances includes the long instrument shown on the right, a 10-foot horn called dung-chen. The compositions performed by the monks are thousands of years old, passed down orally from an original mystical vision by a saint or sage. Monks from Drepung are particularly well known for their chanting—each chanter has learned to sing three tones at once to create a whole chord on their own.

Performing for the people of Boulder

Every performance of ancient temple music and dance by the monks on their visit to Boulder lasts about two hours, with a 20-minute intermission. In the first half, the monks invoke the spirit of goodness before going through several stages of song and dance meant to purify the earth and its people, eliminate negative energy, demonstrate monastic inquiry, and create a harmonious atmosphere. The second part of the performance has four stages: bringing to light the ephemeral nature of everything, releasing the mind from ego, invoking the five elements and five wisdoms, and promoting peace, harmony, and creativity.

Creating harmony with tiny grains of sand

As part of the monk’s trip to Boulder, they spend hours and days creating an intricate sand mandala. The tradition of making these mandalas stretches back more than 2,500 years. Geometric patterns within the mandala represent the floor plan for a sacred mansion and are said to have healing properties for both the monks creating it and the world and its inhabitants at large. The world “mandala” is Sanskrit and means “sacred cosmogram.”

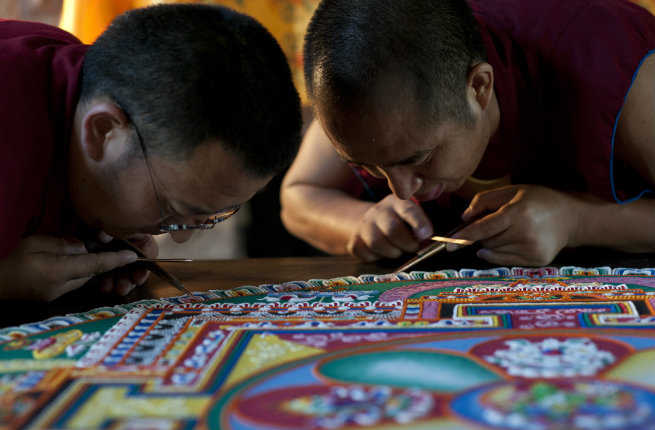

Working on the sand mandala

To make the mandala, the monks first spend several hours drawing the actual design onto the base. It’s measured out with a ruler and compass and drawn with a white pencil. Then, the monks use small metal funnels, called chak-pur, to paint with each color of sand. Sand is the most common, but not always used—in the past, materials like powdered flowers, stones, herbs, grains, and gems were used. Painting begins in the center of the mandala and the monks work their way outward.

The Dalai Lama observes

A photo of the Dalai Lama, who has a residence (and hereditary residence for all future Dalai Lamas) at the monastery in Tibet, watches over construction of the mandala. The Dalai Lama has a great deal of influence over when certain mandalas are used. After the September 11 attacks, the Drepung monks asked him for blessings and advice—he suggested making two different mandalas. One for New York called Yamantaka (The Opponent of Death) and one for Washington D.C. called Buddha Akshobhya (The Unshakable Victor).

Final touches on the mandala

The finished mandala created by the monks measures about four feet by four feet. At this point, it has taken several days of exacting and tedious work to complete the sand construction. Hundreds of types of mandalas exist in the Tibetan Buddhist faith, all with a different purpose, meaning, and intended effect.

Dispersing the destructed mandala

After the mandala is complete, the closing ceremony takes place, where the monks carefully dismantle it and disperse the sand. The process is meant to symbolize the impermanence of everything that exists. All the sand is swept up, half is distributed throughout the audience as blessings, and the remainder is carried in a procession to a flowing body of water. There, they release the sand into the water to spread the healing energies of the sand and the mandala throughout the world.

Meditation in the Utah desert

The monks’ visit to Utah can be busy with performances, blessings, the mandala, and generally interfacing with guests. But they still find time to connect with their faith throughout the surrounding desert landscape. Here, a monk has tucked himself into a rocky pocket to meditate. Tibetan Buddhism generally has two types of mediation—analytical, which is used to examine teachings with an internal point of view, and concentrative, when the monk focuses on one object in their mind until that meditation can be carried out for hours or days effortlessly.